What started as a means to express my observations when riding the Delhi Metro is now about maintaining a not-so-personal diary about the "everyday" Life! Expect a lot of opinions, a love for the unusual, and the tendency to blog on-the-go, unfiltered, with bias, and ALWAYS with a cup of chai...[and some AI]

Can Loving Christmas Eternally Be A Mental Health Thing?

Winter Season 2026 in Delhi: Chikki vs Shelling Peanuts & Eating with Gudd [Shakkar]

Keeping Up With What is Trending: MINIMONY

Why do scratchy people often make you so uncomfortable?

7 Tips to Keep a Straight Face When You Run into Your Ex When Shopping with Your Wife

Do anxious people make for more responsible, safer, or riskier drivers?

WHAT ARE GECKO EYE CAPS, AND WHY IS WATCHING THEM SO SATISFYING?

ENGINE OIL FOR THE BODY: THE CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY OF NASAL RITUALS

7 Ways in Which You Can Pamper Your Prostate Health Every Day after 40s

“Pampering the Prostate: The Quiet Health Ritual Men Refuse to Admit They Need”

Restitude, and Not Moral Rectitude, Is What People Need to Lead Better Lives

7 Types of gym partners you can avoid if you are serious about heavy lifting

7 Ways to Escape Fart-shaming when you can feel the bubbles building up inside!

A Brief History of Gas: How Civilizations Constructed Shame

Humanity did not always pretend that flatulence was a scandal. In ancient Greece, bodily noises were considered signs of vitality; philosophers wrote casually about the body’s expulsions as part of life’s natural functioning. The Roman physician Galen treated digestive gas as an expected product of human physiology rather than a moral flaw. Even the Old Testament mentions flatulence with pragmatic indifference, without attaching stigma. Shame was not the default — it was a cultural invention. The medieval period transformed the body into a moral landscape. Christian monasticism placed heavy emphasis on bodily discipline, self-control, and suppression of earthly urges. Scholars studying medieval bodily regulation note how monasteries structured silence as virtue; noises from the body became intrusions from the lower self, the sinful self. Flatulence transitioned from a natural occurrence to a spiritual weakness. The idea that the body must be subdued, contained, and purified seeped into social norms outside monastic life.

By the Victorian era, fart-shaming had matured into full-blown etiquette. Victorian manuals cautioned against “disruptive bodily functions” as assaults on public decorum. Meanwhile, British colonial power exported these norms globally, shaping bodily etiquette from India to Africa. What had once been a physiological inevitability now carried moral weight. A silent society was a civilized society — or so they insisted.

Yet outside the West, cultural responses varied. Many Indigenous communities treated flatulence with humor rather than shame, seeing laughter as a release valve for the social body. In some Pacific Island cultures, shared bodily humor strengthened interpersonal bonds. Anthropology reminds us: shame is not universal. But globalization ensured that Western bodily norms became the dominant export, and modern flatulence anxiety is, in many ways, a Victorian ghost that survived longer than the empire that birthed it.

The Psychology of Disgust: Why Farts Trigger Social Alarm

Disgust is one of humanity’s oldest emotional warning systems — a survival mechanism designed to keep us away from pathogens long before microscopes could explain why. Psychologist Paul Rozin’s research on core disgust shows that humans are hardwired to avoid anything associated with contamination: rot, feces, spoiled food, bodily fluids, and airborne signals that imply proximity to them.

Flatulence exists in this psychological twilight zone. It does not directly harm, but it represents something potentially harmful. The nose processes it as a micro-alert: “There may be decay nearby.” The mind translates that into social discomfort: “Someone here has crossed an invisible boundary.” The gas itself is harmless; the meaning we attach to it is not.

But disgust alone doesn’t explain fart-shaming. What elevates it to humiliation is metadisgust — the fear of being perceived as disgusting. Humans dread becoming contaminated in someone else’s mental map. The shame is deeply social: being associated with something impure threatens group belonging, a primal need embedded in our evolutionary psychology. Once upon a time, being expelled from the group meant death. Today it means someone side-eyes you on a bus.

What’s striking is that disgust is asymmetrical. We tolerate our own body’s odors far more than those of others. Neurological studies show the brain’s reactions to self-generated smells are muted; identity modulates disgust. But the moment someone else contributes to the air, the amygdala lights up like a ceremonial bonfire. This asymmetry reveals an uncomfortable truth: fart-shaming is not really about gas. It is about the fragile architecture of social identity, where the body becomes a liability we must manage meticulously to remain acceptable.

The Colonial Body: How Western Manners Globalized Bodily Shame

The global spread of fart-shaming is not a natural evolution of etiquette; it is a result of cultural power. During colonization, European norms of bodily control were positioned as superior — cleaner, more rational, more refined — and Indigenous norms were dismissed as primitive. This hierarchy transformed the body into a political symbol. In colonial India, British authorities viewed local bodily practices — burping, spitting, passing gas without theatrics — as signs of uncivilized behavior. Victorian morality seeped into the Indian middle class through schooling, missionary education, and administrative hierarchies. Suddenly, the body that had always been allowed its noises was expected to behave like a machine with muted exhaust.

Similar patterns occurred in West Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Caribbean. Local humor around bodily functions was replaced by imported prudishness. An entire planet gradually internalized the idea that silence equals civilization. Even today, corporate spaces across continents maintain Western behavioral codes: airtight bodily discipline, tacit shame, and the expectation that one must conceal natural functions at all costs. Anthropologists argue that this forced bodily discipline created psychological distance between human beings and their own physiology. The colonized body became something to control rather than inhabit. Fart-shaming is one of its many lasting legacies — a small but persistent reminder of how power rewrites intimacy.

Gender, Power & Who Is Allowed to Make Noise

Fart-shaming is not gender-neutral. Women, across most cultures, face significantly harsher policing of bodily sounds than men. Sociologists note that femininity has historically been associated with cleanliness, delicacy, and restraint — ideals designed for male comfort more than female autonomy. The female body is expected to be an immaculate, scentless, quiet vessel, even though women have the same digestive systems as men and produce the same volume of gas.

Eroticized femininity contradicts biological reality, leaving women in a double bind: to be desirable, they must disavow their own intestines. The pressure is so strong that studies show women are more likely to suppress flatulence in shared spaces, even at the cost of physical pain. Meanwhile, boys grow up normalizing bodily humor, encouraged to treat gas as comedy rather than shame.

Men, however, are not exempt from the politics of noise. Masculinity produces its own paradox: men may joke about farting, but they are shamed when it happens in professional settings where the masculine ideal shifts from boisterous to controlled. The corporate male body must be sealed, efficient, sanitized — no gurgles permitted. Power modifies the rules. A powerful man may get away with a biological slip; a junior employee will not. Bodily noise becomes a class signal: those who must remain silent to keep their jobs cannot afford to be human out loud.

Flatulence, strangely enough, maps social inequality better than many political theories!

The Body Under Surveillance: Why Modern Life Intensifies Gas Anxiety

Modern environments — corporate offices, elevators, co-working spaces, open-plan designs — have turned the body into a performance object. Noise travels farther, privacy is thinner, and the expectation of constant composure is stricter than ever. When our ancestors lived outdoors or in acoustically chaotic settlements, flatulence had far more room to dissipate unnoticed. The modern world, however, traps sound. Air-conditioned conference rooms, metal train compartments, silent hospital waiting rooms — all make the body’s minor rebellions acoustically unforgiving. Today’s social spaces are built for efficiency, not humanity.

Then there’s digital surveillance. Social media thrives on humiliation. A small bodily accident can be filmed, uploaded, shared — a nightmare that inflates shame far beyond its biological relevance. The ancient fear of group exclusion now exists on a global scale. The cost of being the one who “did it” has never been higher.

Urban stress exacerbates digestion. Gastrointestinal researchers note that anxiety slows gut motility, producing more gas and less predictability. The very fear of fart-shaming increases the likelihood of an incident. The body rebels precisely when one needs it to behave. This cycle — anxiety → gas → suppression → more anxiety — is modernity’s gift. Every quiet office becomes a pressure cooker. Every meeting is a Russian roulette of intestinal diplomacy.

Humanity has never been more mechanized on the outside and more turbulent on the inside.

Humor as Sanctuary: The Social Function of Gas Laughter

Despite all the shame, flatulence remains one of the oldest forms of humor. Anthropologists studying tribal rituals, medieval festivals, and contemporary comedy agree on one thing: fart humor is universal, not because it is childish, but because it provides social relief.

Laughter at bodily sounds is not mockery; it is communal acknowledgment of shared biology. It resets the emotional climate. A well-timed laugh abolishes hierarchy, dissolving stiffness between people. The fart joke is a great equalizer — politicians, saints, professors, CEOs, soldiers, monks, and toddlers all emit gas. The humor reminds us that no one escapes the digestive contract of being human.

Some cultures elevate flatulence humor to a ritual. Certain Indigenous groups in North America used gas humor in storytelling as a teaching tool. In parts of Melanesia, exaggerated bodily humor appears in ceremonies to diffuse tension. Even in medieval Europe, fart jokes entered court entertainment — evidence that even royalty secretly granted the body a moment of rebellion.

Humor protects the psyche from shame by converting panic into recognition. When people laugh, the body is absolved. Strangely, humor is the most sophisticated response to flatulence: it is empathy disguised as mischief.

But contemporary society often suppresses bodily humor, replacing it with restraint and silent judgment. This makes fart-shaming more potent — humor was always the pressure valve, and modern adults have been taught to keep it shut.

Rituals of Escape: How Humans Manage the Rising Bubbles

When the intestinal orchestra begins its warm-up, humans employ a wide repertoire of survival techniques. Some are practical; others are pure folklore disguised as strategy. Across interviews, ethnographic notes, and observational studies, a taxonomy emerges.

There’s The Strategic Exit — pretending to take a call, refill a water bottle, or suddenly needing to check something “urgent” at your desk. People learned this maneuver instinctively long before anyone wrote etiquette manuals.

Then comes The Acoustic Masking Technique, where one waits for a loud external noise — a bus rumbling past, someone dropping a book — and releases micro-doses of gas in sync with ambient sounds. This is the jazz improvisation of bodily management: difficult, high-risk, occasionally brilliant.

There is the Postural Shift, a subtle weight redistribution intended to create silence by adjusting pressure on the pelvic floor. Sometimes it works; sometimes it creates a sound reminiscent of a balloon losing hope.

There’s also Cultural Camouflage — in households where cooking smells, festival firecrackers, or crowded gatherings create sensory overload, one blends into the atmosphere. Anthropologists recognize this as environmental opportunism.

But the most human ritual is The Internal Treaty: negotiating with one’s own gut. “Not now, please. I beg you.” It is the closest most adults come to prayer during office hours.

These strategies are often absurd, but they represent the ingenuity of a species desperate to uphold dignity while its intestines conduct their own foreign policy.

The Deeper Anxiety: Why We Fear Being Known Too Intimately

Fart-shaming thrives because it touches a primal nerve: the fear of being fully visible. Humans curate their identities carefully — through clothing, speech, posture, grooming, and social performance. But flatulence is the body’s reminder that identity is porous. The self leaks.

This leakage — literal and metaphorical — threatens the illusion of control. Embarrassment psychologists argue that shame is the emotional response to an unexpected collapse in self-presentation. Farts collapse the boundary between the cultivated self and the biological self. They reveal that beneath the polished persona is a digestive tube like everyone else’s.

For many, this exposure feels like intimacy before consent. It is being known too quickly, too truthfully. Flatulence forces vulnerability, which is why the shame cuts deeper than the act deserves.

But interestingly, intimate relationships often use bodily functions as milestones of trust. Couples who can laugh about gas tend to report higher relational satisfaction. Friendship deepens when people can be biologically honest around one another. Children bond through shared humor about bodily sounds long before they develop mature emotional language.

This suggests that fart-shaming is not inevitable. It is a cultural imposition, not a psychological necessity. The body doesn’t see shame in gas; society teaches us to.

Humans fear flatulence not because of the noise or smell, but because it reveals a truth we spend our lives avoiding: we are more animal than we admit.

Final Reflection Module

Somewhere between biology and etiquette, between instinct and embarrassment, the sound of gas escaping a human body becomes a quiet story about culture, power, intimacy, and vulnerability. Flatulence is not an offense; it is a reminder that the boundaries of selfhood are fragile and endlessly negotiated. Every bubble rising through the gut is an echo of the ancient tension between the disciplined body society demands and the untamed body evolution left us with. If there is an art to escaping fart-shaming, it lies not in tightening every muscle but in loosening the grip on dignity just enough to acknowledge that being human is messy, noisy, and occasionally hilarious — and that maybe the shame was never biologically ours to carry.

References (20 sources)

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/ae.2008.35.2.171

- https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/emo

- https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-11373-007

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/behavioral-and-brain-sciences

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5579396/

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0191886916305705

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/26295410

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00223980.2018.1468336

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352154618301844

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-36114-5

- https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle

- https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/44442371

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10410236.2019.1574140

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/41471532

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07481187.2018.1443715

Not Sure if Amitriptyline Suits Your Symptoms? Scan My Tryptomer Experiences

The old-world charm has perhaps faded away entirely, but it is effective for me, where I have a combination of GAD and anxiety-linked IBS. There is something surprisingly effective about how Tryptomer has helped me in controlling diarrhea-predominant IBS symptoms. That constant sense of worry about untimely bowel movement and sudden changes in body weight was first controlled via Tryptomer. Initially, when my symptoms were acute, I needed as much as 75 mg Tryptomer daily, divided across 3 equal doses of 25 mg each. It takes a bit of time to build up. Give it a week, and if you have been suffering from IBS associated with anxiety or depression, Tryptomer should give you some remarkable results.

Never take it on an empty stomach! This is one rule I have followed for the longest time. Take it after meals, and be patient with it. Tryptomer will get the job done, but if you suffer from acute panic attacks, this is not the best option. For me, getting hooked on to Tryptomer happened after trying and failing at least 4 other prescription drugs, including Valium, Anti-Dep, Tancodpe, and Fluoxetine. Valium is just a short-term sedative at best. I believe it presents the highest chance of abuse. When you are really choking with anxiety, any medication that can give you quick symptomatic relief also presents a higher probability of causing substance abuse. This is where I have done well to be patient, giving each of the prescription drugs for anxiety control some time before trying the next one.

Tryptomer has a stomach-binding effect. Hard to explain in strictly medical terms, but understand it like this - it tends to tighten up and cement the nerves that connect your gut to your mind. This is as basic a definition as you will find online. As a result, the typical symptoms of IBS-D associated with long-term sufferers, such as acidity, bloating, undigested food, and cramping, are controlled with Tryptomer. Yes, the pitfall of sudden weight gain is there, but it is not the drug alone that is at work. Like most psychotic medications, Tryptomer can make you a bit sleepier, and this is when your daily schedule should help you keep away from gaining too much. For many people, Tryptomer is an outdated medication for those with classical, textbook symptoms of depression or anxiety, but for me, it has really worked!

If you tend to believe medical wisdom borrowed from Google searches, you are likely to find that Tryptomer has been used for migraine prevention and for serious sleep issues. The latter scenario might still work in higher dosages. But, to be used as a means of extreme, splitting headache caused by a flare-up at home or office? Tryptomer would not be my recommendation!

- AVAILABILITY: not that easy to find in Delhi NCR.

- EASE OF USE: try to take it after meals.

- SIDE EFFECTS: dry mouth and bloating might happen at the outset.

- SEDATION ISSUES: not that serious.

- ANTI-DEPRESSANT EFFECTS: moderate to good over a period.

- ANXIETY CONTROL EFFECTS: good in low dosages and longer periods.

- IBS CONTROL CAPABILITIES: impressive for IBS-D sufferers.

- INSOMNIA SUPPORT: reasonably good without being extreme.

- CONSTIPATION PROBABILITY: a bit higher than other substitutes.

- KICK-IN PERIOD: at least a week, as a minimum.

- RANGE OF INTERACTIONS: not much, rather limited.

Is It True That the Eldest Daughters in a Big Family Make for the Best Spouses?

For the Karwa Chauth Enthusiasts: There Is No Real Karwa Maa/Maata, Right?

The Goddess Who Wasn’t There

In classical Hindu texts, every fast has a presiding deity. Ekadashi bows to Vishnu. Shivratri to Shiva. Karwa Chauth, on paper, bows to nothing specific. The word “Karwa” itself simply means a clay vessel — karva, the same pot used to store water or grains. The “Chauth” marks the fourth day after Purnima in the month of Kartik. Combine them, and what you get is a pot and a date — not a goddess. The ritual was originally a symbolic gesture of abundance and community sharing among women — wives of soldiers, they say, who would send these pots filled with food or water to their husbands stationed far away. Over time, a vacuum emerged. Humans dislike ritual without personality. So the imagination supplied one — Karwa Maa, the invisible guardian of faith, fasting, and fragile husbands. She was never canonized, but she didn’t need to be. Devotion gave her birth, and insecurity gave her purpose.

Why Do Some People Hug the Edge While Others Own the Middle? The Psychology of Driving Alignment

Are They Helpless or Hustling? The Uncomfortable Truth of Urban Begging in India

From Windshield Morality to Street-Level Reality

The judgment many Indians make at traffic signals—are they helpless or hustling?—is not simply a snap moral verdict; it’s a story we tell ourselves to live with contradiction. Researchers call one engine of that story the just-world hypothesis: the comforting belief that, broadly, people get what they deserve. When that belief is threatened by visible suffering, people explain it away—by inflating the supposed failings of those who suffer, or by minimizing their own obligation to respond. In the micro-theater of a red light, this bias is reinforced by compassion fade and the identifiable-victim effect: we feel for the single vivid face but shut down as the faces multiply, converting a human encounter into a policy problem that belongs to “the government.” None of this proves that every beggar is honest or coerced; it shows that most drivers’ certainty about who is “faking” is often a psychological convenience more than an evidence-based conclusion. To get past convenience, we have to look beyond the glass: at data on homelessness and homelessness, at migration and disability, at the legal status of begging, and at how cities actually work for people with no cushion.

Counting the Unseen: What the Numbers Say (and Don’t)

India’s official lens on the street poor is imperfect by design; the homeless are hard to count and easy to ignore. The 2011 Census enumerated 1.77 million homeless people nationwide—about 15 per 10,000—with 938,000 in urban areas; Uttar Pradesh and Maharashtra led absolute counts, and sex ratios were starkly skewed among the homeless. Civil society networks argue the true figures run higher, and city-level snapshots are volatile: Delhi has swung from ~16,000 in a DUSIB 2014 count to claims of 150,000–300,000 sleeping rough in recent surveys and press reports; the range itself signals chronic under-measurement and policy drift. Meanwhile, a nontrivial share of people on pavements are interstate migrants, the mentally ill, the elderly without kin, and people with untreated disabilities—groups that face the sharp end of urban informality. Data gaps do not absolve anyone; they indict our measurement priorities. If we cannot even agree on how many are outside, our debates about “rackets” risk substituting suspicion for statistics.

(Sources: Census 2011 homeless abstracts; HLRN briefings; recent reportage on Delhi homelessness.)

Law and Order—or Order without Law? The 2018 Decriminalization and After

For decades, Indian states relied on the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, 1959 (and its extensions) to arrest, detain, and “rehabilitate” people for the act of asking for alms. In 2018, the Delhi High Court in Harsh Mander & Karnika Sawhney v. Union of India struck down key provisions of this law as unconstitutional—holding that criminalizing begging punishes people for systemic failures and violates the right to life and dignity. Journalistic and legal commentary called it a watershed: the capital could no longer treat destitution as a crime. In 2021, amid COVID-era pleas, the Supreme Court added an important note of caution: the Court “would not take an elitist view” to ban begging, emphasizing that people beg in the absence of education and employment, and directing governments to focus on vaccination and rehabilitation rather than removal. Decriminalization, however, is not the same as support. Without robust shelter capacity, mental-health services, and income pathways, the end of arrest simply leaves people to the same signals. The law can stop adding harm; it cannot by itself create help.

(Sources: Delhi HC judgment; Reuters coverage; legal analyses; SC remarks reported by national dailies.)

From Bhiksha and Dāna to the Red Light: India’s Long History of Alms

To see roadside begging only as a nuisance is to forget India’s civilizational memory of alms giving. In Hindu traditions, bhiksha (alms) and dāna (charity) emerge from Vedic and classical texts, mapping a repertoire that includes support for renunciants, students, and the poor; in Buddhism, dāna is the first perfection and the beginning of a moral path; in Sikhism, langar collapses hierarchy through shared food; in Islam, zakat binds the prosperous to the needy. That history does not sanctify every knock on the glass; it contextualizes it. Colonial and post-colonial governments reframed mendicancy as a problem of order, severing alms from ethics and poverty from policy. Today’s discomfort—“shouldn’t they work?”—is an inheritance of that pivot. Our past recognized the poor as a moral claim on the community; our present often treats them as an administrative inconvenience. The question is not whether alms “solve” poverty (they do not). It is whether a society with deep traditions of giving can modernize its compassion without outsourcing it to suspicion.

(Sources: doctrinal overviews of bhiksha/dāna; cultural essays on Indian giving; Buddhist teachings on dāna.)

Economics at the Signal: Informality, Income, and the ‘Racket’ Narrative

Few topics inflame middle-class conversations like the “organized begging mafia.” Rigorous, national-scale evidence is thin; local police busts and investigative features do find coercive rings that exploit children or the disabled. There are also credible studies documenting forced begging as trafficking, particularly of minors. But between the denial (“it’s all genuine”) and the generalization (“it’s all a racket”), reality is mixed. The informal economy is India’s largest employer of last resort; for those shut out—because of injury, addiction, psychosis, documents, language, caste prejudice—begging is sometimes the only remaining margin. Daily “earnings” vary wildly by city, junction, time, and police pressure; the modal state is not scam, but precocity. A serious response must do two things at once: prosecute coercion where it exists, and provide exits where it does not. Otherwise, the “mafia” story becomes a moral alibi that lets cities ignore the far larger population of unorganized, unprotected poor in plain sight.

(Sources: social-science papers on begging in India; policy briefs; SSRN/legal overviews on trafficking/forced begging.)

Disability, Illness, and the Edges of Employability

One reason the “just get a job” refrain rings hollow is that a visible share of beggars are people with disabilities—amputations, untreated infections, congenital impairments—often compounded by mental illness or substance dependence. India’s labor market is unforgiving even for the able-bodied poor; for those with psychosis, epilepsy, or intellectual disability, reality is brutal: employers shun, families fracture, documentation lapses, medication is unaffordable, relapse is frequent. Women face layered risks: abandonment, intimate-partner violence, trafficking, and the burdens of caregiving without cash. When “employability” is invoked as a cudgel, it ignores these frictions. Any ethical urban response has to start with low-barrier shelters, assertive outreach, harm-reduction, and ID recovery, and only then speak of skilling. A city that cannot keep someone clean, fed, and medicated cannot credibly demand productivity from them.

(Sources: homelessness and shelter reports; ministry briefs; clinical and NGO literature on mental illness and street survival.)

Why We Doubt: Just-World Beliefs, Compassion Fade, and the Single Face

Back at the red light, psychology explains some of our worst instincts. The just-world bias pushes us to assume people deserve their lot; scope insensitivity dulls our empathy as numbers rise; the identifiable-victim effect makes us more generous to the single story than the crowd. We also rationalize non-giving with stories of fraud, whether or not we’ve verified them. These cognitive shortcuts serve a purpose: they protect us from burnout and help us navigate relentless exposure to need. But they also distort moral vision, turning structural failures into individual blame. The antidotes are not heroic: give through channels you trust; if you decline, do so without contempt; stay curious about the causes you cannot see; and remember that evidence beats anecdotes. The person at your window is neither proof that charity works nor proof that it doesn’t; they are evidence that the social contract frays exactly where the city is most shiny.

(Sources: classic and contemporary research on just-world beliefs; compassion fade; identifiable-victim literature.)

Children at the Window: Protection First, Not Policing Alone

Nothing polarizes drivers like children selling pens or tapping on glass after 10 pm. The Juvenile Justice framework and anti-trafficking laws already recognize child begging as exploitation, requiring rescue, shelter, and family tracing. But “rescue” is not a photo-op; without follow-through—de-addiction, schooling, case-work, income support for families—children boomerang back to the same junctions, now smarter and more cynical. The public dramatizes “drugging rings” (some cases are real), yet often ignores migratory poverty that pushes families to put children to work. Effective city practice looks boring: night shelters that are safe, bridge schools, cash-plus support for caregivers, and police trained in child protection, not harassment. Outrage fades when the signal turns green; the child’s problem does not.

(Sources: JJ Act materials; NGO field reports; trafficking literature and media reports.)

Policy Pivot: From Handcuffs to Rehabilitation (The SMILE Experiment)

If criminalization failed, what replaces it? The Union government’s SMILE umbrella scheme (Support for Marginalized Individuals for Livelihood and Enterprise) launched in 2022 includes a sub-scheme for the Comprehensive Rehabilitation of Persons Engaged in Begging (guidelines updated Oct 2023). It funds identification, counseling, shelter, skilling, and reintegration through local bodies and NGOs. Early numbers suggest ambition exceeds capacity: one independent analysis cites roughly 9,958 people identified across 81 cities, with ~970 rehabilitated—a start, not a solution. City showcases (e.g., Indore’s “beggar-free” claim) report training, product lines, and family reunification; other cities are just beginning baseline surveys. SMILE’s promise is in coordination—health, police, child-protection, shelters, IDs, jobs—yet that is precisely where Indian urban governance frays. Decriminalization opened the door; delivery will decide whether people step through it.

(Sources: official SMILE pages, guidelines, and PIB notes; independent policy analyses; recent news on city pilots.)

Era-Gone-By vs. Today: From Mendicants to Margins of the Metropolis

In older India, the mendicant occupied a paradoxical prestige: renunciation conferred moral authority, and giving to the monk was a merit practice. Urban modernity flips the valence: market logic prizes productivity; the non-earning poor become an eyesore, not an ethical claim. The same society that funds temple kitchens and gurudwara langars flinches at a boy knocking on an SUV window. This is not hypocrisy so much as dislocation: the institutions that historically managed charity (kinship, guild, temple, monastery) cannot absorb the scale and anonymity of migrant mega cities. The old script—householders give, monks receive—doesn’t cover a metropolis where the mendicant is neither monk nor neighbor. If we want compassion that fits the city, we must update the channels: cashless street-giving into verified funds, corporate kitchens linked to shelters, municipal dashboards that show real-time needs, and philanthropy that flows to boring operations, not just branded moments.

(Sources: cultural histories of alms; contemporary urban policy commentary.)

What Drivers Can Do: Between Cynicism and Sentimentality

Two reflexes fail us at red lights: sentimentality (give indiscriminately to feel good) and cynicism (never give because “it’s all a scam”). A saner middle path starts with clarity: if you choose to give in person, prefer food, water, sanitary supplies, or QR-linked donations to vetted shelters; if you choose not to, don’t demean. Support night-shelter ecosystems, harm-reduction, and community kitchens that outlast a signal cycle. Vote and volunteer for city capacity: shelters with women-safe spaces, mental-health linkages, and outreach teams that speak migrants’ languages. Ask your ward Councillor one boring question: How many functional shelter beds exist tonight within 3 km, and who checks? Above all, keep judgment provisional. A society that sees every beggar as a thief will design policy like a lockbox; a society that sees every beggar as a saint will neglect systems. The work is to build systems sturdy enough that neither myth is necessary.

(Sources: practice notes from shelters and city pilots; behavioral science on giving.)

The Hardest Sentence: Some Are Coerced, Many Are Cornered

Yes, coercion exists; yes, there are gangs; yes, children are exploited. These require policing that is rights-literate and prosecutions that stick. But the larger truth is duller and more devastating: many who beg are cornered by structural scarcity—no address to get an ID, no ID to get a benefit, no benefit to stop a slide. Others are pulled under by illness, addiction, grief, or disability. To call this “easy money” is to confess distance from the street. None of this obliges anyone to hand out coins at signals; it obliges a city to stop recycling the poor between junctions, lock-ups, shelters, and pavements. When you feel the urge to explain away the hand at your window, try a harder thought: what would it take for this person to not be here next month? If your answer begins and ends with “they should work,” you have described your hope, not their options.

Reflection: The Glass is Thinner Than It Looks

The moral comfort of the driver’s seat is an illusion. The glass is not a wall; it is a lens that magnifies our stories about worth, work, and waste. The beggar might be hustling, helpless, coerced, recovering, or simply surviving today to try again tomorrow. The city will contain all of these truths until it chooses an architecture of care strong enough to make signal-side charity unnecessary. Until then, our ethics at red lights should be modest: refuse contempt, resist convenient myths, and route generosity into channels that outlast a green light. The goal is not to romanticize begging or giving; it is to retire the question by building a city where no one has to ask it.

References

- Delhi High Court Judgment (Harsh Mander & Anr. v. UOI & Ors., 08 Aug 2018) – PDF copy via HLRN: https://hlrn.org.in/documents/HC_Delhi_Decriminalisation_of_Begging.pdf

- Harsh Mander & Anr. vs UOI & Ors., text via Indian Kanoon: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/117834652/

- Reuters (Thomson Reuters Foundation). “Begging is not a crime, Delhi High Court rules.” https://www.reuters.com/article/world/begging-is-not-a-crime-delhi-high-court-rules-idUSKBN1KU1FG/

- IDR (India Development Review). “The decriminalisation of begging.” https://idronline.org/decriminalisation-of-begging/

- Supreme Court remarks on pleas during COVID (“won’t take an elitist view”): Times of India report. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/cant-take-elitist-view-to-ban-begging-supreme-court/articleshow/84809917.cms

- The Economic Times (SC remarks, 27 Jul 2021). https://m.economictimes.com/news/india/wont-take-elitist-view-of-banning-beggars-from-streets-says-sc-on-plea-for-their-rehab-amid-covid/articleshow/84785407.cms

- NDTV (SC remarks). https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/wont-take-elitist-view-of-banning-beggars-from-streets-supreme-court-2496375

- Census of India 2011 – Houseless (PCA HS, district level): https://censusindia.gov.in/nada/index.php/catalog/5047

- Census summary (houseless overview). https://www.census2011.co.in/houseless.php

- HLRN (Homelessness overview; urban numbers). https://hlrn.org.in/homelessness

- Population Association of America paper (houseless metrics based on 2011). https://paa2019.populationassociation.org/uploads/190986

- Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment – SMILE scheme overview. https://socialjustice.gov.in/schemes/99

- SMILE sub-scheme guidelines (Comprehensive Rehabilitation of Persons Engaged in Begging). https://grants-msje.gov.in/display-smile-guidelines

- PIB press release on SMILE allocations (12 Feb 2022 launch; outlays). https://www.pib.gov.in/Pressreleaseshare.aspx?PRID=1806161

- Lok Sabha starred question annex (SMILE-B guidelines issued 23.10.2023). https://sansad.in/getFile/loksabhaquestions/annex/183/AU3583_HdFtsx.pdf?source=pqals

- IMPRI policy note on SMILE outcomes and constraints (2025). https://www.impriindia.com/insights/support-marginalized-individual-scheme/

- Just-world hypothesis primer and sources (Lerner 1980; Rubin & Peplau 1975). https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/just-world-hypothesis

- Lerner, M. J. The Belief in a Just World (book chapter overview). https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4899-0448-5_2

- Identifiable-victim/singularity effects (open-access article, 2024). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10977801/

- Meta-analysis on compassion fade (2019). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749597818302930

- Wisdom Library – Bhiksha (concept and sources). https://www.wisdomlib.org/concept/bhiksha

- Overview of alms giving traditions (Hindu/Buddhist context). https://www.hinduwebsite.com/buddhism/practical/dana_praciceofgiving.asp

- SSRN article (legal status, organized exploitation, SMILE). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/5208299.pdf?abstractid=5208299&mirid=1

- Social Science Journal PDF (2020) on begging causes/implications incl. organized exploitation claims. https://www.socialsciencejournal.in/assets/archives/2020/vol6issue6/9041-535.pdf

- Times of India (2025) – City-level homelessness and shelter capacity debates (Delhi). https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/lakhs-homeless-in-delhi-little-planning-on-their-relief/articleshow/121523850.cms

- Times of India (2025) – Indore’s SMILE showcase as “beggar-free city.” https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/indore/indore-shows-the-way-to-a-beggar-free-city-at-national-workshop/articleshow/122394750.cms

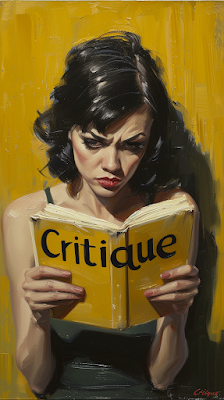

A little bit of criticism ain't that bad - just get better at processing it!

Let us have a bit of a chat about dealing with criticism.

It's one of those things that can really sting, ain't it? When your flatmate moans about the rubbish or your boss pulls you up on a missed email, it's easy to start wondering if they secretly can't stand you. Those little comments can trigger all sorts of negative thoughts about ourselves that have been buried away. Maybe you fixated on that one critical bit in your performance review because deep down, you doubted you were really cut out for the job. Or perhaps, having the right critical parent growing up means any suggestion about your cleaning habits feels like a massive blow to your self-worth. The truth is that we cannot always get top marks, no matter how hard we try to be perfect little angels. So, we must learn how to handle criticism without letting it chip away at our confidence. Next time you're feeling like a proper muppet or a total failure - trust me, you're not - give these expert tips a go:

It can also help to get a second opinion from someone you trust. Having that different perspective might make you realize your self-criticism is a bit harsh or one-sided. They might point out that the remark was just about a specific behavior, not a judgment on you as a person. Instead of ruminating on what went wrong, shift your focus to what you can change going forward. Whether it's better time management, being more reliable, or actively working on a weakness, taking positive steps to improve is a huge confidence booster and reminds you that you're in control. And don't forget to give yourself some credit where it's due! Make a list of your strengths and qualities that you're properly proud of - maybe it's your creative spark, your wicked sense of humor, or your ability to keep challenging yourself. Reminding yourself of what makes you brilliant helps drown out those negative voices.

By putting strategies like these into practice, you'll slowly get better at taking criticism on the chin and using it as a chance to grow, instead of letting it derail you completely. We all drop the ball sometimes, but a few stumbles don't make you a lost cause, do they? Just dust yourself off and keep being your fabulous self!

This also means you need to realize that coping with criticism is a challenge for everybody: Differential Coping Strategies.

Different roles within the healthcare sector, such as doctors and nurses, tend to adopt different coping strategies. For instance, doctors may prefer planning-based strategies, while nurses might lean towards behavioral disengagement and self-distraction, especially under the pressure of direct patient care during the pandemic (Frontiers).

Studies have shown that roles like nursing can experience heightened emotional responses, such as fear and nervousness, compared to other healthcare roles. This variation often relates to the direct intensity and nature of patient care involved (PLOS.

A scoping review of the nursing workforce during COVID-19 highlighted significant psychosocial challenges and emphasized the importance of effective coping strategies to mitigate the adverse effects on mental health. This synthesis pointed out the need for better support systems and tailored interventions for nurses (BioMed Central).

Positive coping mechanisms, such as seeking social support and practicing self-care, have been associated with lower levels of distress and somatization among healthcare workers. Conversely, negative coping mechanisms can exacerbate stress and emotional turmoil (Frontiers).

Reduced Self-Esteem and Confidence: Persistent criticism, particularly when it is harsh or unjustified, can erode a person's self-esteem and confidence. This often results in feeling undervalued and can impair one's ability to perform tasks confidently (Core Themes).

Emotional Exhaustion: Dealing with ongoing criticism can be emotionally draining. This constant stress can lead to emotional exhaustion, making it difficult for individuals to engage fully with their work or to bring enthusiasm and energy to their job roles (Core Themes).

Impact on Physical and Mental Health: Constant workplace stress, including stress from not effectively handling criticism, can lead to serious health issues such as anxiety, depression, and even physical symptoms like headaches and sleep disturbances (SkillsYouNeed).

Decreased Productivity and Engagement: When criticism is not constructive and is perceived as a personal attack, it can lead to decreased motivation and productivity. Employees might also feel less committed to their roles and disengage from work-related activities (Core Themes).

The journey to handle criticism begins during childhood itself, and the inability to handle it can affect the individual:

Self-Esteem and Self-Image: Persistent criticism in childhood can lead to long-lasting self-esteem issues and a negative self-image. Individuals who experience frequent criticism from caregivers often develop chronic self-criticism, which can persist into adulthood, making them overly sensitive to rejection and highly self-critical in all areas of life (Psychology Today).

Emotional and Behavioral Impact: Verbal abuse, a form of criticism, during childhood is associated with an increased risk of developing emotional disorders such as anxiety and depression. It can also impact behavioral development, leading to increased aggression, withdrawal from social interactions, and difficulties in managing emotions and forming healthy relationships (Psychology Today)

Cognitive Development: Harsh criticism during critical developmental periods can adversely affect cognitive development. Children subjected to frequent criticism may face challenges in academic settings, struggle with attention and learning, and have a higher risk of developing cognitive impairments that can affect their educational and occupational outcomes (Psychology Today).

Understanding how the human brain processes criticism involves complex interactions between various brain regions, particularly those related to emotional and cognitive responses. Here's a breakdown based on recent scientific research:

Emotional and Cognitive Integration: Contrary to older theories that suggested separate areas of the brain handle emotion and cognition independently, recent studies indicate these functions are highly interdependent. For instance, during emotional responses, both the amygdala (involved in emotional reactions) and cortical areas (associated with cognitive processing) are active. This shows that emotional and cognitive processes are intertwined, particularly in how we process and react to criticism (Frontiers).

Prefrontal Cortex and Criticism: The prefrontal cortex plays a crucial role in processing criticism, linking it to higher cognitive functions such as decision-making and social behavior. This area of the brain helps us to interpret the emotional content of criticism and determine appropriate responses, integrating emotional reactions with logical reasoning (Journal of Neuroscience). Contemporary media uses words like social fitness as a means to signify social interactions and the complexity of it, and that this is a challenge for most folks, and yes, it requires a bit of effort to get good at it for most people!

Adaptive Responses: The human brain is adaptive, utilizing feedback from the environment (including criticism) to adjust behaviors and predictions about future outcomes. This adaptive process involves a complex interplay between the brain’s predictive coding and emotional valuation systems, helping individuals learn from past experiences and adjust future behaviors accordingly (Frontiers).

Volition and Action: Research into voluntary actions, such as how we choose to respond to criticism, shows that these are influenced by both underlying motivations and available cognitive strategies. This involves areas of the brain responsible for planning and executing actions based on anticipated outcomes, highlighting the sophisticated nature of human response mechanisms (Journal of Neuroscience).

Neurological Development and Social Cognition: Studies have also shown that social cognitive abilities, which are crucial for interpreting and responding to criticism, develop through complex changes in brain activity over time. These abilities are crucial for understanding others’ perspectives and intentions, which are central to processing social cues like criticism (MIT Technology Review).

We've all been there - that sinking feeling when someone points out our shortcomings or suggests we could've done better. For some, it's water off a duck's back. They can take the feedback on board, maybe feel a twinge of disappointment, but ultimately brush it off without too much bother. But for others, criticism can feel like a brutal attack, unleashing a tsunami of negative emotions and self-doubt. So why do some people seemingly crumble at the first sign of reproach?

The Seeds of Sensitivity

One of the biggest factors is how we develop our self-esteem and resilience growing up. Those who had a childhood plagued by relentless, harsh criticism from parents or authority figures often internalize those voices, becoming their own toughest critics as adults. With every negative remark, it can feel like that emotional wound is being reopened and reinforced. On the flip side, kids raised by nurturing parents who offset criticism with genuine praise and reassurance tend to be better equipped to put feedback into perspective as adults. Having that solid foundation of self-worth acts as a buffer against feeling crushed by critiques.

The Perfectionist's Paradox

For the perfectionists among us, criticism can be utterly destabilizing. These are the folks who set sky-high standards for themselves and simply can't countenance any implication that their work or efforts fell short of flawless. Perfectionists often equate failure with being a failure, unable to separate their self-worth from outcomes. Even constructive feedback can trigger an existential crisis.

At its core, hypersensitivity to criticism frequently stems from deeply rooted insecurities about not measuring up or being inherently inadequate in some way. Those who struggle with self-acceptance tend to internalize any negative comments as confirmation of their secret fears about not being good/smart/talented/resilient enough. What's intended as an opportunity for growth gets filtered through a distortion of self-doubt.

When Egos Run Wild

Paradoxically, those with oversized egos and an excessive need to be revered can also exhibit thin skin around criticism. Unable to tolerate anything that contradicts their aggrandized self-image, these individuals dismiss or angrily lash out at feedback, seeing it as an unforgivable slight against their superiority. For them, criticism isn't something to learn from, but a threat to be neutralized at all costs.

The Inner Critic's Greatest Hits on Repeat

While the delivery certainly matters, sometimes it's not so much the external criticism itself that cuts deep, but how it aligns with our own pummeling inner voice. We all have that persistent internal narrator replaying our perceived flaws and failures on an endless loop. When someone's words seem to harmonize with those toxic refrains in our heads, it can feel like a brutal validation of our worst self-criticisms.

Making Criticism Sting a Little Less...

The bottom line is that none of us is immune to criticism, as unwelcome as it can feel. But by developing self-compassion, surrounding ourselves with positive influences, and learning to separate feedback from self-worth, we become better equipped to take those tough comments in stride. It's never easy, but building our resilience helps criticism sting a little bit less over time.

Must-Read Books on

Handling Criticism

How to Win Friends and Influence People — Dale Carnegie

One of the oldest and most respected self-help classics teaches practical ways to deal with people, improve interpersonal skills, and handle criticism without defensiveness. It emphasizes avoiding needless criticism and fostering sincere appreciation.

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck — Mark Manson

A bestselling, counterintuitive guide to prioritizing what truly matters, which includes letting go of others’ negative judgments and not letting criticism derail you.

Daring Greatly — Brené Brown

Focuses on vulnerability and courage. Understanding vulnerability can help you take criticism in stride rather than seeing it as a threat to your self-worth.

Self-Compassion: Stop Beating Yourself Up and Leave Insecurity Behind — Kristin Neff

Not strictly about criticism from others, but mastery of self-compassion builds the emotional foundation to weather external critique without collapsing inwardly.

On My Own Side: Transform Self-Criticism and Doubt into Permanent Self-Worth and Confidence — Dr. Aziz Gazipura

Directly tackles inner self-criticism and negative self-talk that makes external criticism feel worse.

Unmasking the Inner Critic: Lessons for Living an Unconstricted Life — Andrew Lang

Offers guidance on breaking free from the inner voice that amplifies criticism and fear.

Taming Your Gremlin — Rick Carson

A practical, psychologically rooted book on identifying and quieting the internal voice that magnifies criticism and undermines confidence.

Coping With Criticism — Jamie Buckingham

Focuses specifically on how to emotionally and mentally receive criticism without fear, and respond with honesty and humor.

The Power of Positive Criticism — (Author varies by edition)

A straightforward book on reframing criticism as useful feedback instead of something destructive.

I’m OK – You’re OK — Thomas A. Harris

A classic on self-esteem that indirectly strengthens your ability to take criticism without personal collapse.

.png)